A centenary approaches: on the morning of 8th February 1913 gardeners arrived at work at a large hothouse complex in London to find glass broken in three houses, orchids removed from their pots and the pots broken, and plant labels removed. ‘An attack on plants is as cowardly and cruel as one upon domestic animals or those in captivity’, snorted the Gardeners’ Magazine. Garden staff were helped in their investigations not only by the police, but by the perpetrators themselves: clues were some ‘feminine fingerprints’, a handkerchief, a bag, and an envelope bearing the inscription Votes for women ‘in an uneducated hand’. The Daily Express has always had a taste for a sober and reasoned headline, and on this occasion it read ‘Mad women raid Kew Gardens!’

In case anyone was in any doubt, the Raiders of the Bust Pot returned to Kew twelve days later and burned down the refreshment pavilion, strewing placards for women’s suffrage nearby.

This time the raiders were caught. The Morning Post reported the trial on 8th March:

At 3.15 next morning one of the night attendants noticed a bright light inside the pavillion and running towards the building he saw two people running away from it. He blew his whistle and did his best to extinguish the fire, which immediately broke out, but his efforts were unavailing. At this time two constables happened to be in the Kew-road, and after their attention had been attracted to the reflection of the fire in the sky, they saw two women running away from the direction of the pavillion. The constables gave chase, and just before they caught them each of the women who had separated was seen to throw away a portmanteau. At the station the women gave the names of Lilian Lenton – who was too ill to appear before the Magistrate on remand – and Joyce Lock, the accused, who later gave her correct name of Olive Wharry.

According to the Roger Fulford in his history Votes for Women:

A girl [sic – she was then 27], Olive Wharry, was arrested and brought before the local magistrates’ court. She threw a directory at the head of the chairman, Councillor Bisgood. Although she aimed from a distance of six feet, she fortunately missed her target.

Olive Wharry was sentenced to eighteen months in prison. The plan of her companion, Lilian Lenton. had been to burn two buildings a week in order to make Britain ungovernable – and a few depotted orchids can only have hastened that goal.

We do miss the daring and novel tactics of the suffrage movement – where is this energy these days? Other acts in early 1913 listed by Roger Fulford include the action of a Miss Melford:

the daughter of a leading actor, perched…on the top deck of a motor-bus…from this vantage point she drove along Victoria Street, firing stones from a powerful catapult into the windows of the buildings passed by the bus. The professionals at many of the golf courses around Birmingham were startled to find that some of their putting-greens had, during the night of January 30th been burned by acid with the slogan ‘Votes for Women’..

And what were the results of this bold and imaginative campaign? Ray Desmond’s Kew: a history of the Royal Botanic Gardens goes straight to the core issue, but is phlegmatic : ‘The destruction of the Pavilion was no great loss. It had been crudely fabricated ….’

Were Kew – and golf courses for that matter – plucked out of the air as targets? Or chosen solely for maximum public impact? Not only for those reasons – Kew also had ‘form’ as far as women were concerned. Here, from Desmond’s history of Kew, are the views of Sir Joseph Hooker, the former Director of Kew, as reported in a letter in 1902:

At one time some women (not ladies in any sense of the word) gardeners were employed at Kew but there are none now. Sir Joseph says he could not possibly recommend any lady to go there. She would have to work with the labouring men, doing all they have to do, digging, manuring, and all the other disagreeable parts of gardening. Then there is the work in the hothouses; the men, I believe, work simply in their trousers, and how could a lady work with them.

As I’ve mentioned in another post (here), the cultivation of orchids was also a particularly male obsession, and one to which well-off gentlemen devoted much more time and resources than to getting a women’s suffrage bill passed by Parliament. If you want to get a man’s attention (if not his goodwill), kick him in the orchids – that’ll teach him to garden in his trousers.

Today’s plant is of course an orchid: Anacamptis pyramidalis. It’s maybe the most common orchid round my way, so it wouldn’t have excited much attention from the gentlemen orchid collectors. I see it often in grassy roadside verges, sometimes in quite large groups.

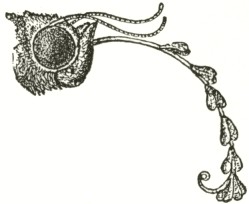

‘We now come to Orchis pyramidalis, one of the most highly organised species which I have examined’ wrote Charles Darwin in his On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fe rtilised by insects (1862, available at Darwin online here). He noticed that the flowers were so successful at attaching their pollen sacs to the proboscis of visiting moths that some of these were so encumbered they must have found it hard to feed.

Head and proboscis of Acontia luctuosa with seven pair of the pollinia of Orchis pyramidalis attached to the proboscis

Let’s update the daring woman theme. Betty Carter was one of the most independent of all jazz singers – she not only created her own style and led her own trios, but founded her own record company, BetCar. I’ve always liked this song, from the album of the same name: ‘Droppin’ things’. It brings back the images of the broken pots, and just when you think she’s playing the dizzy woman lost in love, she sings the lines: ‘now the table’s turned, he knows not to fool around…’