I’ve just had what will probably be my botanical experience of the year. I know this sentence, which is meant to be puffed up into a superlative, has its own deflating word, and that’s ‘botanical’, rather than, say, ‘spiritual’, but maybe there was some of that, too.

Friends here have told me before that to see spring flowers, I should go to the Sauveplaine – the generally but sparsely wooded limestone plateau above the plain and the garrigue, the name coming from the Latin sylva plana, a wooded plain. The last weekend I did just that, together with a group of friends, led by the most experienced local botanist, our retired village nurse.

I was struck by awe. So many plants, so many flowers, such beauty in such profusion. It was like stumbling into Eden, or an eco-warrior’s dreamed-of future, yet just a couple of hundred metres along a dirt track from a road we travel several times a week. It’s not marked on the map, and the name isn’t even in the dictionary. To remind us that we weren’t in another reality, or in paradise, there were electricity pylons.

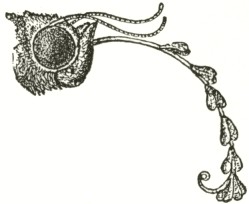

But still: pyramidal orchids as common as daisies, drifts of white lilies, and a field turned azure by a haze of viper’s bugloss, which reminded me of a comment about this plant (Echium vulgare) on this blog from Ceridwen. After a while, a long while, my serious side resumed control of my wondering brain, and I started to list the plants I recognised. Within about a fifty metre radius, by the end of the morning I had a list of 54 species.

Why such diversity here? As Xavier, the geologist in our group, explained, it’s partly because near our village one set of rock strata was carried over another, resulting in much folding and breaking, complicated by later volcanic activity – we have at least three extinct volcanic hills. This results in a very varied set of soil types, including acidic schist and alkaline limestone, but all of which are very porous, meaning that the hilltops especially are very dry. Plants which settle on the Sauveplaine thus have to be able to resist long periods of drought, which favours plants with bulbs and tubers, such as lilies or the orchids I wrote about in the last post. Ironically, because the water has drained to underground reserves, the area is described in our village brochure as ‘un veritable chateau d’eau’ – a real water tower – because it supplies the village spring: la source de la Resclause.

Other plant adaptations to drought include having taproots (such as bugloss or mountain lettuce), or very long root systems such as most legumes: a lucerne plant just 30cm high can have roots many metres long. Or seeing out the drought as seeds, which means the whole vegetative life-stage has to be completed in the spring. Or having tiny, wax-covered, or hairy leaves which reduce water loss and enable the plant to be almost dormant during la grande chaleur (thyme and cistus are examples) Additionally, some of the plants which smother everything else at lower or wetter levels are absent, giving all these dry-adapted flowers a chance. The proper botanical term for this sort of shrubland vegetation is not garrigue or Sauveplaine, but the Spanish word matorral.

I also noticed a few dry-stone walls up there, presumably for penning animals, meaning the area was used perhaps up to 100 years ago for winter pasture for sheep and goats, of which there used to be many in the village, though there are none now. Grazing would have stopped the succession of the flora to trees and shrubs, and the dry stony ground will take a long time – centuries more – to revert to a covering of holm oak, lentisk, broom and arbutus. Wildfires also turn back the clock of reversion to forest (there were four large fires up there in 2011), but untouched the area will slowly revert: it’s a place in transition.

The special nature of this habitat made me think of a project I’ve had in mind since I read this post on a blog I very much enjoy, The Reremouse, (http://thereremouse.wordpress.com/) written by a nature conservation worker in Walsall in the English Midlands. As you’ll see if you follow the link, she suggests an alternative to aimless trainspotterish plant collecting, which is to concentrate on a particular delimited patch and record all species found there. In her own list she includes animals and fungi, of which she has good knowledge, but I’m thinking of doing this just for the flora of the Sauveplaine.

I think there are some benefits of this sort of project: it forces me to look at less showy species, such as grasses, or ones which are more difficult to identify (oh, the problems I’ve had with yellow compound flowers!) It reminds me of the extent of plant diversity in a small area. I can see what arrives and what disappears. It should make me more aware of zones within the habitat such as shade/full sun, and different soil types. I’m getting quite keen on the idea. In fact, I’ve already started another plant patch list for a small area of coastal sand dunes, about which you can expect to hear more.

I wondered about choosing music which was sufficiently awestruck, but I’ve settled for a local band we’ve seen a couple of times and like very much. Their music – some composed by the band, some traditional – is rooted in this area and in this sort of scenery – their name, Du Bartas, means ‘in the bushes’ in Occitan, and they sing mostly in that language. This video looks as if it was recorded in a shed up in the hills:

Coming up soon: In the dunes – botanising among the tourists